Thursday, March 19, 2009

Sunday, March 15, 2009

David, Robby, Dan, Beth and the Johns save lives while on vacation

Recently, our MS-2 class finished winter quarter and moved one precarious step closer to the wonders of clinical Candyland and all its third-year clerkship glory. To celebrate this historic accomplishment, several of our noble band – including Dan, Old John, Stalker-y John, Robby, and Beth (Mrs. Robby) – traveled to Montana for a manly wilderness adventure. (Kevin wasn’t allowed because the state of Montana has an Asian quota that was met when I joined the trip).

This sort of trip means several things: (1) an ungodly amount of pork consumption (Beth managed to create this); (2) an uncomfortable amount of “That’s what she said" jokes; (3) a nonstop country music bonanza; and (4) 5 med students and an RN (who knows approximately 4.3x more than the rest of us combined) having nerdy faux-medical debates for 4 days.

After a productive morning of snowy adventuring (them) and sleeping (me), we cranked up the country and were treated with a stirring performance of Rascal Flatt’s “Skin,” which tells the story of Sara Beth and her fight against an unknown hematologic malignancy.

We did what any reasonable Spring Breakers would and beat the song to death with the following lively discussion:

After listening to the song, one thing’s for sure: someone’s a poor historian. Seriously Sara Beth, how can we help you without more details? Associated symptoms? Fatigue or fever? Throw us a bone. And Rascal Flatts, did you even go to med school? This OCP is just awful. Even the referring physician’s dropping the ball (“Between the red and the white cells, something’s not right?” At least give us a blood smear.). Clearly we have to do all the work…

First, Sara Beth’s only a teenager, so we’re immediately thinking ALL.

Easy bruising? Sounds like thrombocytopenia.

Mixed “red and…white cell” involvement? Could be an expected pancytopenia.

An aggressive chemotherapeutic regimen with a ~70% cure rate (lowered to "six chances in ten" for Sara Beth due to her older age and its negative prognostic contribution)? Perhaps a little CVAD induction therapy.

If needed, we’ll be ready for marrow transplant on second remission after relapse.

Go enjoy your prom, Sara Beth. We’ve got it from here. Now, if you’ll excuse us, the kid from "John Q" needs a cardio consult for his hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and then we’ve got a 3 o’clock to get a CD4 count from Andrew Beckett in "Philadelphia."

Your son's next, Denzel...

This sort of trip means several things: (1) an ungodly amount of pork consumption (Beth managed to create this); (2) an uncomfortable amount of “That’s what she said" jokes; (3) a nonstop country music bonanza; and (4) 5 med students and an RN (who knows approximately 4.3x more than the rest of us combined) having nerdy faux-medical debates for 4 days.

After a productive morning of snowy adventuring (them) and sleeping (me), we cranked up the country and were treated with a stirring performance of Rascal Flatt’s “Skin,” which tells the story of Sara Beth and her fight against an unknown hematologic malignancy.

We did what any reasonable Spring Breakers would and beat the song to death with the following lively discussion:

After listening to the song, one thing’s for sure: someone’s a poor historian. Seriously Sara Beth, how can we help you without more details? Associated symptoms? Fatigue or fever? Throw us a bone. And Rascal Flatts, did you even go to med school? This OCP is just awful. Even the referring physician’s dropping the ball (“Between the red and the white cells, something’s not right?” At least give us a blood smear.). Clearly we have to do all the work…

First, Sara Beth’s only a teenager, so we’re immediately thinking ALL.

Easy bruising? Sounds like thrombocytopenia.

Mixed “red and…white cell” involvement? Could be an expected pancytopenia.

An aggressive chemotherapeutic regimen with a ~70% cure rate (lowered to "six chances in ten" for Sara Beth due to her older age and its negative prognostic contribution)? Perhaps a little CVAD induction therapy.

If needed, we’ll be ready for marrow transplant on second remission after relapse.

Go enjoy your prom, Sara Beth. We’ve got it from here. Now, if you’ll excuse us, the kid from "John Q" needs a cardio consult for his hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and then we’ve got a 3 o’clock to get a CD4 count from Andrew Beckett in "Philadelphia."

Your son's next, Denzel...

Labels:

David,

Med School,

Movies

Monday, March 9, 2009

David tells you what to do (in an admissions interview)

Previously, I’ve given advice of variable seriosity to pre-medical students, both here and in person, usually with respect to the MCAT, personal statement, and general application process. This year, due to a clear administrative error in the selection process, I was allowed to join our school’s admissions committee to serve as a student interviewer. In addition to granting me a golden opportunity to implement my subversive personal agenda, this position has further demonstrated how important the interview is in the admissions process and where applicants commonly stumble or succeed in separating themselves from the pack.

When Kevin and I are asked to speak to pre-meds about admissions, people often think of the interview as a high-stress, nebulous obstacle shrouded in enigmatic mysteriousness with a black-boxy finish. To assuage these concerns, and so that future generations of medical students will learn from those who came before, I present a few suggestions for anyone with an upcoming med school interview:

1) Prepare, prepare, prepare:

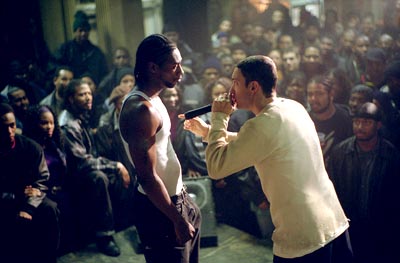

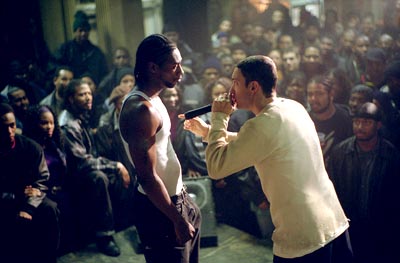

This one’s obvious, right? In med school interviews, as in “8 Mile,” you only get one shot. You spent weeks/months preparing for the MCAT and years kicking ass in your science courses, during extracurricular activities, and while saving babies in the free health clinic you established in between curing cancer and playing varsity lacrosse for a school that isn’t Duke. That work ethic is what got you to the interview in the first place, so don’t abandon it now. You’d be surprised how often people seem un- or underprepared to discuss the most basic topics they MUST know will be coming down the question pipeline. There is a 105% chance you’re going to be asked why you want to go into medicine, why it excites you, and what experiences led you to the decision that the next 7+ years of training and three subsequent decades of practice are what you want to do with your life. Think about how you’d answer these questions and practice discussing them in some sort of mock interview format. You don’t need a canned script, but if you don’t have a compelling reason why you want the MD, why would the admissions committee make one up for you?

Along these lines, make sure you’re familiar with the specific program for which you are interviewing. Why does the curriculum appeal to you? What’s unique to that school that will help you reach your professional goals and why are your strengths well suited to that school? This stuff is coming, so you might as well prepare for it. Be Eminem vs. Papa Doc, not Proof. (RIP, Proof.)

Your interview should be like this, but less profane and with fewer tanktops.

2) Research the health care system:

This is an extension of (1); you’re entering a system almost universally recognized as broken, with a myriad of significant issues and just as many proposed solutions. As Atul Gawande once said, “The infrastructure and delivery of American health care are wack, yo*.” This issue is all over the news and, more importantly, is going to affect you every day of your professional life. So spending 10 hours reading about our system and its major pros/cons, about the employees who studied in online medical coding courses, nationalized health programs implemented abroad, recent legislation, etc., would be extremely high-yield. And really, it’s not like anyone expects the applicant to solve the health crisis in one hour. Still, it’s reasonable to expect a candidate to be familiar with the major issues of the profession she wishes to enter; it shows the applicant cares and, just as significantly, that she took the effort to prepare for the interview.

3) Be honest:

Adcoms interview a lot of people. They hear a lot of stories and develop a sensitive radar for half-truths and general BS. If you don’t know in what or if you want to specialize, I think that’s fine, but a vague story about how reconstructive surgery is your calling will ring hollow if you have no experiences to back it up. If you get asked a factual question you can’t answer or are asked to discuss something that requires background information you don’t know, it’s better to admit it and ask for what you need or discuss ways you’d obtain the information required than to make stuff up on the fly. No one expects you to have all the answers. If you did, there’d be no need for med school. You’d just stop by the front desk for a white coat and board certification and be on your life-saving way.

4) Be engaging:

An interview is as much about figuring out who you are and how you interact with others as it is a discussion of your credentials / experiences. An interview is inherently subjective. Think about what types of interviewer-interviewee discussions would positively resonate with an interviewer when he or she evaluates a candidate. An applicant who is warm and personable makes a more favorable impression than one who is excessively reserved. Sure, the interview is serious, and it might not be the time for a risqué joke, but it’s still important to connect with your audience. Your demeanor during the interview can provide a window into how compassionate you might be with patients and how well you’d interact as part of a small team. Don’t affect insincere enthusiasm, but try your best to enjoy the interview and show your true personality. Smiling doesn’t hurt.

All of the above may seem intuitive, but you'd be surprised how often otherwise well-qualified candidates struggle in these areas. Mostly it appears to be an issue of preparation, so spend as much time thinking/talking through these issues as you can. It will definitely pay off in the end.

*He didn’t really say this. I think it was actually part of the Flexner Report…

When Kevin and I are asked to speak to pre-meds about admissions, people often think of the interview as a high-stress, nebulous obstacle shrouded in enigmatic mysteriousness with a black-boxy finish. To assuage these concerns, and so that future generations of medical students will learn from those who came before, I present a few suggestions for anyone with an upcoming med school interview:

1) Prepare, prepare, prepare:

This one’s obvious, right? In med school interviews, as in “8 Mile,” you only get one shot. You spent weeks/months preparing for the MCAT and years kicking ass in your science courses, during extracurricular activities, and while saving babies in the free health clinic you established in between curing cancer and playing varsity lacrosse for a school that isn’t Duke. That work ethic is what got you to the interview in the first place, so don’t abandon it now. You’d be surprised how often people seem un- or underprepared to discuss the most basic topics they MUST know will be coming down the question pipeline. There is a 105% chance you’re going to be asked why you want to go into medicine, why it excites you, and what experiences led you to the decision that the next 7+ years of training and three subsequent decades of practice are what you want to do with your life. Think about how you’d answer these questions and practice discussing them in some sort of mock interview format. You don’t need a canned script, but if you don’t have a compelling reason why you want the MD, why would the admissions committee make one up for you?

Along these lines, make sure you’re familiar with the specific program for which you are interviewing. Why does the curriculum appeal to you? What’s unique to that school that will help you reach your professional goals and why are your strengths well suited to that school? This stuff is coming, so you might as well prepare for it. Be Eminem vs. Papa Doc, not Proof. (RIP, Proof.)

Your interview should be like this, but less profane and with fewer tanktops.

2) Research the health care system:

This is an extension of (1); you’re entering a system almost universally recognized as broken, with a myriad of significant issues and just as many proposed solutions. As Atul Gawande once said, “The infrastructure and delivery of American health care are wack, yo*.” This issue is all over the news and, more importantly, is going to affect you every day of your professional life. So spending 10 hours reading about our system and its major pros/cons, about the employees who studied in online medical coding courses, nationalized health programs implemented abroad, recent legislation, etc., would be extremely high-yield. And really, it’s not like anyone expects the applicant to solve the health crisis in one hour. Still, it’s reasonable to expect a candidate to be familiar with the major issues of the profession she wishes to enter; it shows the applicant cares and, just as significantly, that she took the effort to prepare for the interview.

3) Be honest:

Adcoms interview a lot of people. They hear a lot of stories and develop a sensitive radar for half-truths and general BS. If you don’t know in what or if you want to specialize, I think that’s fine, but a vague story about how reconstructive surgery is your calling will ring hollow if you have no experiences to back it up. If you get asked a factual question you can’t answer or are asked to discuss something that requires background information you don’t know, it’s better to admit it and ask for what you need or discuss ways you’d obtain the information required than to make stuff up on the fly. No one expects you to have all the answers. If you did, there’d be no need for med school. You’d just stop by the front desk for a white coat and board certification and be on your life-saving way.

4) Be engaging:

An interview is as much about figuring out who you are and how you interact with others as it is a discussion of your credentials / experiences. An interview is inherently subjective. Think about what types of interviewer-interviewee discussions would positively resonate with an interviewer when he or she evaluates a candidate. An applicant who is warm and personable makes a more favorable impression than one who is excessively reserved. Sure, the interview is serious, and it might not be the time for a risqué joke, but it’s still important to connect with your audience. Your demeanor during the interview can provide a window into how compassionate you might be with patients and how well you’d interact as part of a small team. Don’t affect insincere enthusiasm, but try your best to enjoy the interview and show your true personality. Smiling doesn’t hurt.

All of the above may seem intuitive, but you'd be surprised how often otherwise well-qualified candidates struggle in these areas. Mostly it appears to be an issue of preparation, so spend as much time thinking/talking through these issues as you can. It will definitely pay off in the end.

*He didn’t really say this. I think it was actually part of the Flexner Report…

Labels:

David,

Kevin,

Med School,

Premed Advice

Wednesday, March 4, 2009

Kevin is unimpressed with some of his future colleagues

Recently David and I went with many of our classmates to a medical student research conference to present the groundbreaking research we all did this summer. There aren't a lot of requirements for submitting an abstract but nevertheless it’s a great opportunity to waste 4 days in a cool location meeting students from other medical schools and boozing it up at night. At the end of the weekend you get your “research” abstract published in a journal that will likely benefit no one. But we're really hoping JAMA accepts Beef Stew.

Anyone presenting at this conference is assigned a specific time slot which falls into one of many half-day time blocks at various rooms/locations around the conference site. The format is rather simple, you give a 10 minute talk followed by 3 minutes for questions from the audience. Our school was very insistent about students maintaining a certain level of professionalism at this event. Most of it is pretty straight forward: wear a suit, be respectful, don’t be drunk during the day. Easy. They were also especially adamant about students attending the entire half-day session they were assigned to rather than just showing up for your specific time slot then peacing out after the 15 minutes was up.

All this seems straight forward and self-apparent but not so for some of our colleagues from other medical schools... especially this one from the north. Instead of waking up early and showing up at the start of the half day session, these kids would swoop in about 5 minutes before their slotted time. Inevitably 10 of their classmates would also march in to root them on. When it was his turn the main kid would give his schpiel aboot his research into something related moose-related hunting injuries. Then as soon as his/her presentation was done, the entire posse would stand up and dash out before the moderator could make a passive-aggressive plea for students to stay.

Anyone presenting at this conference is assigned a specific time slot which falls into one of many half-day time blocks at various rooms/locations around the conference site. The format is rather simple, you give a 10 minute talk followed by 3 minutes for questions from the audience. Our school was very insistent about students maintaining a certain level of professionalism at this event. Most of it is pretty straight forward: wear a suit, be respectful, don’t be drunk during the day. Easy. They were also especially adamant about students attending the entire half-day session they were assigned to rather than just showing up for your specific time slot then peacing out after the 15 minutes was up.

All this seems straight forward and self-apparent but not so for some of our colleagues from other medical schools... especially this one from the north. Instead of waking up early and showing up at the start of the half day session, these kids would swoop in about 5 minutes before their slotted time. Inevitably 10 of their classmates would also march in to root them on. When it was his turn the main kid would give his schpiel aboot his research into something related moose-related hunting injuries. Then as soon as his/her presentation was done, the entire posse would stand up and dash out before the moderator could make a passive-aggressive plea for students to stay.

So essentially a large gaggle of students would loudly file in during the middle of another student’s presentation, stay for 15 minutes for their friend's topic, then make a run for it when the next student is setting up his slides. Way to go guys.

*I just wanted to add that while I witnessed a few of these incidents, personally I was not a victim since there were no students from that school scheduled after me.

Labels:

David,

Kevin,

Med School

Saturday, February 28, 2009

Julia knows exactly the kind of doctor she will become

"Sorry, can't educate you about this Fragile X Syndrome your baby boy has, but I CAN talk to you about German health care reforms from 2003-2007."

Ladies and gentlemen, since you were aghast at the long silence on this blog, let me tell you what has been keeping our two class-clowns from their ranting: our med school’s obligatory course on health care structure, policy, and reform*.

Yes, this is a good idea at its core… after all, if we didn’t know anything about the organizations that will be paying us some day that would be pretty lame. However, this class is decidedly a scheduling bully—perhaps a little insecure about itself, and therefore going to make your life miserable to puff up it’s own sense of self-importance. Weekly quizzes requiring recall of minute details from the readings and lecture slides? Awesome. In-class “debate” group presentations, where the professor may-or-may-not call you a liar? Hmm… alright, I guess... Arbitrarily restrictive, two-page, double-spaced paper proposing 1-3 major health care reforms, while giving background and then providing objections to it? Ugh, just leave me alone already!

This class single-handedly managed to eat up more time weekly than musculoskeletal, genetics, and hematology combined!

So, while that pain in your shoulder causing you to be unable to raise your arm to shoulder-level may be very concerning… Can I interest you in a discussion on the pros-and-cons of a physician’s duty to follow public health mandates during a disaster?

Ladies and gentlemen, since you were aghast at the long silence on this blog, let me tell you what has been keeping our two class-clowns from their ranting: our med school’s obligatory course on health care structure, policy, and reform*.

Yes, this is a good idea at its core… after all, if we didn’t know anything about the organizations that will be paying us some day that would be pretty lame. However, this class is decidedly a scheduling bully—perhaps a little insecure about itself, and therefore going to make your life miserable to puff up it’s own sense of self-importance. Weekly quizzes requiring recall of minute details from the readings and lecture slides? Awesome. In-class “debate” group presentations, where the professor may-or-may-not call you a liar? Hmm… alright, I guess... Arbitrarily restrictive, two-page, double-spaced paper proposing 1-3 major health care reforms, while giving background and then providing objections to it? Ugh, just leave me alone already!

This class single-handedly managed to eat up more time weekly than musculoskeletal, genetics, and hematology combined!

So, while that pain in your shoulder causing you to be unable to raise your arm to shoulder-level may be very concerning… Can I interest you in a discussion on the pros-and-cons of a physician’s duty to follow public health mandates during a disaster?

Labels:

Guest Authors,

Med School

Monday, February 16, 2009

David fails to understand honors (/pass/fail grading)

In the long months since Kevin's illuminating "year 2 is just year 1's uglier, more high-maintenance sister" entry, we have received countless e-mails with pressing questions and comments about the absence of irreverent med school insider-y wit filling the empty spaces in the lives of our devoted public. Here's a sampling of our fan mail:

Whyyyyyyyyyyyyyy???!!!!!

- Julia

I miss you guys so much it hurts sometimes.

- Jess

My one goal in life is to live long enough to see just one more post.

- John (the old one, not the stalker-y one)

Well, the posting drought ends now. RIP, John. (Oh, and Kevin has promised to write several more posts in the near future, though the quality may not rival 'year 2/year 1' brilliance.)

-------------------------------------------------

Second year, in all of its we-survived-first-year-and-now-we’re-almost-to-third-year glory, has added a new wrinkle to our academic lives: the ‘H.’ Whereas our med school employed a strictly Pass-Fail system during year one, we now face the world-altering prospect of a 50% increase in the number of possible grades. And though popular wisdom places these grades well down the totem pole of importance in one’s residency application, most students are nonetheless interested in filling their transcripts with as many pre-clinical H’s as they can muster.

The logic behind second year grades seems pretty clear: after a transitional first year where mastery of basic concepts is most important, an H/P/F system gives students a chance to distinguish themselves as the material becomes more advanced/clinically relevant. It rewards those who make the extra effort to excel, and such sustained motivation can only have a positive influence on one’s ultimate clinical competence.

Grading systems are designed to both motivate students and, by definition, stratify them based on performance. Grades provide valuable feedback to students and also give administrators at the next step in the academic ladder an essential signal about student achievement. There’s a reason med schools don’t let pre-meds take their pre-reqs P/F; a P only indicates the student demonstrated the minimum competence required to complete the course. Student X may have excelled or almost failed, but no one can know for sure within a purely P/F system.

The major downside of the H/P system is that, though it provides more information than the P/F system, it falls short of a third choice with a full range of grades (akin to the GPA system in college or HS) for no real reason. If adding the H makes sense, why not just take the plunge to a 4.0 scale with the traditional complement of +/-‘s? The purpose of grading is to provide valuable information to all interested parties: to students about their performance, to teachers about how well the material is being learned, to residency administrators about the academic prowess of prospective applicants, etc. If information is the goal, what benefits are there to purposefully providing less information in an H/P/F-only system*? Here are a few I’ve heard, but for the most part, they don’t stack up to deeper review:

1) The H/P/F system is less stressful.

In our system, a final grade of 90% or above usually qualifies one for honors. There may be extra essays involved to reach the holy honors land, but there’s always a numerical cut-off that separates the two strata. Thus, grading is essentially an all-or-none exercise. There is really no major difference in mastery between someone who scores 90% and someone with an 89.1%, yet there’s a reasonable chasm in their ultimate grades. The person with the 90% is in rarified air. The sub-90 % kid is left with a grade that is indistinguishable from a 70% effort. Compare this to a system in which 89% is a B+ and the resultant grade-point differential of a question or two is far less consequential. Which one is more stressful?

2) The H/P/F system motivates students to excel.

Though this is true, it fails to acknowledge that a more traditional grading system incorporates the same educational incentives without dragging along a few major downsides. In a typical 4.0 system, a student who gets an 85% in every class collects a series of B’s that ends up numerically equivalent to a colleague who gets half A’s and half C’s. In the H/P/F system, the former is left with a dreaded P-fest (teehee) while the latter gets rewarded with 50% H’s. Yet who is really the better student? The person who does consistently well but never aces anything or the one who completely ignores half of his classes in order to honor the other half? There may be no clear answer, but it is intuitively obvious that the H/P/F system incentivizes just this sort of all-or-none effort. Grades can both motivate students toward better performance and lead them to utilize practical ways to game the system.

3) It doesn’t really matter; preclinical grades are of little importance and it’s what you learn that determines how you perform when it really counts (during Step 1 and on the wards).

Sure, those other things are more important predictors of matching success than the preclinical transcript, but that doesn’t mean the latter is insignificant. At our school, preclinical grades factor into the behind-closed-doors ranking system that determines whether or not we’re eligible for AOA, which almost everyone agrees is a meaningful distinction. And regardless of how much they ‘matter,’ we should still try to find the best way to dole ‘em out.

4) Stop ranting and go do something useful like studying.

OK fine, you win. But instead of studying, I’m going to figure out if there’s some sort of 15-15-1 equivalent to residency applications…

*It’s not even so much, or at all, about how high the ‘H’ threshold is – it’s actually a lot easier to honor any given class at our school relative to the stories I’ve heard from friends at other institutions – but rather about the utility of the H/P/F system itself.

Whyyyyyyyyyyyyyy???!!!!!

- Julia

I miss you guys so much it hurts sometimes.

- Jess

My one goal in life is to live long enough to see just one more post.

- John (the old one, not the stalker-y one)

Well, the posting drought ends now. RIP, John. (Oh, and Kevin has promised to write several more posts in the near future, though the quality may not rival 'year 2/year 1' brilliance.)

-------------------------------------------------

Second year, in all of its we-survived-first-year-and-now-we’re-almost-to-third-year glory, has added a new wrinkle to our academic lives: the ‘H.’ Whereas our med school employed a strictly Pass-Fail system during year one, we now face the world-altering prospect of a 50% increase in the number of possible grades. And though popular wisdom places these grades well down the totem pole of importance in one’s residency application, most students are nonetheless interested in filling their transcripts with as many pre-clinical H’s as they can muster.

The logic behind second year grades seems pretty clear: after a transitional first year where mastery of basic concepts is most important, an H/P/F system gives students a chance to distinguish themselves as the material becomes more advanced/clinically relevant. It rewards those who make the extra effort to excel, and such sustained motivation can only have a positive influence on one’s ultimate clinical competence.

Grading systems are designed to both motivate students and, by definition, stratify them based on performance. Grades provide valuable feedback to students and also give administrators at the next step in the academic ladder an essential signal about student achievement. There’s a reason med schools don’t let pre-meds take their pre-reqs P/F; a P only indicates the student demonstrated the minimum competence required to complete the course. Student X may have excelled or almost failed, but no one can know for sure within a purely P/F system.

The major downside of the H/P system is that, though it provides more information than the P/F system, it falls short of a third choice with a full range of grades (akin to the GPA system in college or HS) for no real reason. If adding the H makes sense, why not just take the plunge to a 4.0 scale with the traditional complement of +/-‘s? The purpose of grading is to provide valuable information to all interested parties: to students about their performance, to teachers about how well the material is being learned, to residency administrators about the academic prowess of prospective applicants, etc. If information is the goal, what benefits are there to purposefully providing less information in an H/P/F-only system*? Here are a few I’ve heard, but for the most part, they don’t stack up to deeper review:

1) The H/P/F system is less stressful.

In our system, a final grade of 90% or above usually qualifies one for honors. There may be extra essays involved to reach the holy honors land, but there’s always a numerical cut-off that separates the two strata. Thus, grading is essentially an all-or-none exercise. There is really no major difference in mastery between someone who scores 90% and someone with an 89.1%, yet there’s a reasonable chasm in their ultimate grades. The person with the 90% is in rarified air. The sub-90 % kid is left with a grade that is indistinguishable from a 70% effort. Compare this to a system in which 89% is a B+ and the resultant grade-point differential of a question or two is far less consequential. Which one is more stressful?

2) The H/P/F system motivates students to excel.

Though this is true, it fails to acknowledge that a more traditional grading system incorporates the same educational incentives without dragging along a few major downsides. In a typical 4.0 system, a student who gets an 85% in every class collects a series of B’s that ends up numerically equivalent to a colleague who gets half A’s and half C’s. In the H/P/F system, the former is left with a dreaded P-fest (teehee) while the latter gets rewarded with 50% H’s. Yet who is really the better student? The person who does consistently well but never aces anything or the one who completely ignores half of his classes in order to honor the other half? There may be no clear answer, but it is intuitively obvious that the H/P/F system incentivizes just this sort of all-or-none effort. Grades can both motivate students toward better performance and lead them to utilize practical ways to game the system.

3) It doesn’t really matter; preclinical grades are of little importance and it’s what you learn that determines how you perform when it really counts (during Step 1 and on the wards).

Sure, those other things are more important predictors of matching success than the preclinical transcript, but that doesn’t mean the latter is insignificant. At our school, preclinical grades factor into the behind-closed-doors ranking system that determines whether or not we’re eligible for AOA, which almost everyone agrees is a meaningful distinction. And regardless of how much they ‘matter,’ we should still try to find the best way to dole ‘em out.

4) Stop ranting and go do something useful like studying.

OK fine, you win. But instead of studying, I’m going to figure out if there’s some sort of 15-15-1 equivalent to residency applications…

*It’s not even so much, or at all, about how high the ‘H’ threshold is – it’s actually a lot easier to honor any given class at our school relative to the stories I’ve heard from friends at other institutions – but rather about the utility of the H/P/F system itself.

Labels:

David,

Med School

Monday, December 15, 2008

Kevin realizes year 2 is just year 1's uglier, more high-maintenance sister

Finals are finally over and that's the conclusion I've reached.

Labels:

Kevin,

Med School

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)